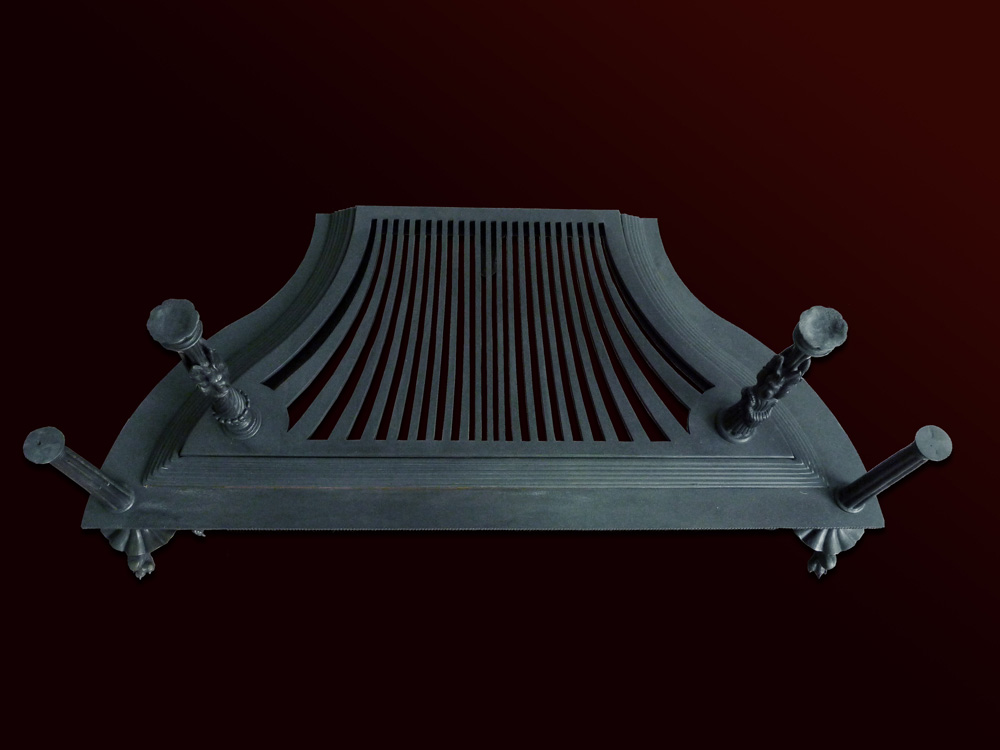

In Diverse Maniere Piranesi is anxious to point out that he has given particular prominence to his designs for chimneypieces. Since this form of interior feature appears to have had no precedent in antiquity, it can effectively demonstrate the imaginative application of the past to a strictly contemporary requirement. Moreover, as he astutely observed in the inscription on one of the plates (Wilton‑Ely 867), the chimneypiece is a particularly important focus for ornamentation in England. There is also an etched chimneypiece for Abbondio Rezzonico in the Diverse Maniere, according to a caption. Piranesi was not primarily concerned with narrow issues of antiquarian scholarship but with the evolution of a new language of design in emulation of what he identified as the Roman approach to design. Many of the designs are so excessive they can hardly be considered in good taste. The main ingredient was imaginative design, often unreservedly capricious. The virgin territory of fireplace design gave him the freedom to allow his fantasy to run riot. Egyptian and Etruscan elements merge with the myths of antiquity and the renaissance. In Piranesi’s virtuoso rococo style the language of the chimneypiece found its first great master. Of the designs featured in Diverse Maniere, sixty‑one are designs for fireplaces, eleven of them in a flamboyant Egyptian style. Two of these designs are known to have been made, one for the Earl of Exeter (now in Burghley House) and the other for John Hope. Piranesi was both an astute businessman and a charismatic presence, ‘perfettissimo matto in tutti’ – the most perfect madman in everything. He was ‘by nature an irrepressible talker, bubbling over with information and speculative theories, and he was often viewed as tiresome, volatile, and disorganised in Roman academic circles’ (Roland de Leeuw, Dealer and Cicerone, from Piranesi as Designer). It is not surprising that responses to his work were sharply divided. The academic painter James Barry (1741–1806) was one of his fiercest critics. He saw capitals carved ‘in so fantastic a manner with so little of the true forms remaining, that they serve indifferently for all kinds of things, and are with ease converted into candelabra, chimney pieces, and what not. Examples of this kind of trash may be seen in abundance in the collections of Piranesi’. Horace Walpole, writing about the designs of Robert Adam in his Anecdotes on Painting (1780 edition), saw a more inspired and digested taste emerging from the hand and mind of Piranesi. The romantic, even gothic dimension to Walpole and his circle seems to identify something in Piranesi which is classical in its inspiration but almost anti-classical in its sensibility. ‘This delicate redundance of ornament growing into our architecture might perhaps be checked, if our artists would study the sublime dreams of Piranesi, who seems to have conceived visions of Rome beyond what it boasted even in the meridian of its splendour. Savage as Salvator Rosa, fierce as Michel Angelo, and as exuberant as Rubens, he has imagined scenes that would startle geometry, and exhaust the Indies to realise. He piles palaces on bridges, and temples on palaces, and scales Heaven with mountains of edifices. Yet what taste in his boldness! What grandeur in his wildness! What labour and thought both in his rashness and details!’ Piranesi’s fireplace designs gave him the opportunity to let his imagination run free. There was no history of previous designs to respect, and no function to fulfil other than providing a mantelpiece and embellishing a fire opening. He was able to create visionary designs that transformed C18th English stately homes. John Martin (1789–1854) and Gustav Doré (1832–83) and the sublime imagination of the C19th can be seen to build upon Piranesi’s imaginative freedom. Piranesi provided abundant material for the Hollywood designers of the early C20th. Set designers for cinema, and designers of cinema buildings, were able to plunder the source material he offered and achieve the sense of scale and awe he imagined. Piranesi never comments directly on Assyrian art, but the designs for D W Griffiths’ film masterpiece Intolerance (1916) capture the scale and potent virility Piranesi associated with the classical world. Now, at the start of the C21st, in a digital world which crumbles boundaries between disciplines and dominates with the mediation of information, Piranesi’s preoccupations with knowledge and imagination seem more relevant than ever. An interpretation of the Chimneypiece In each of the interpretations of the objects, we have attempted to follow Piranesi’s lead and maintain the playful incorporation of references to develop a new visual language utilising the full palette of tools that are now at our disposal. The faces of the angels at the top are based on Iberian, Roman and Greek ideals, while the two Medusa heads at the bottom are based on 3D scans of real faces that are used in their raw form, complete with all the ‘artifacts’ (technical or equipment errors) of the scanning process. Cornucopias pouring forth fruitfulness incorporate a mix of organic computer modeling and 3D scans of actual fruit: the idealised is merged with the real. The sheep’s heads at each corner were modeled on the basis of their similarity to a Border Leicester sheep with its characteristic arched nose. The horns of a number of breeds were closely studied and a stylised horn form was derived to match Piranesi’s print. Two cameos in the centre of the fireplace, indicated in Piranesi’s print only by a few sketchy lines, have been replaced with a 3D scan of a coin minted as a bit of Reformation propaganda. A topsy‑turvy pope/devil head makes an oblique reference to the role of coins in bridging the conceptual gulf between sculpture and printmaking. To complement the fireplace, a suitably understated set of fire furniture was selected from the many examples in the Diverse Maniere. Piranesi’s print shows this fireplace design set against a wall covered with a Pompeian-style decoration similar to, but more cluttered than, the Etruscan dressing room at Osterley Park built in 1775 to a design by Robert Adam. As in many of the designs, the fire is shown without a grate, made directly on the floor, with a beautifully observed depiction of smoke, staying within the frame of the fireplace.

|